No matter how strange the framing, there was usually a figure or an element

that centred the scene, the surface of the painting. The colours were

generally faded, and the attention was focussed on the conditions of

presenting a hyper-processed image. Questions also came up at that time

about the material properties of what was being seen and about the limits of

vision, of observation, because the image was fleeting, blurred, in muted

tones. What seems to have changed since then is that the focus – from the

realisation of the work to how the viewer experiences it – has shifted from

the result to the process of producing the painting. Since 2014 or 2015,

it’s the making of the work that stands out, or better, what is seen is the

course of the painting, the painting in process.

But that’s not all. Now, the work no longer seems to be aimed at

constructing a predetermined, integral image that is clearly outlined, or

even recognisable, as it did before. On the contrary, the process has

started to comprise varying degrees of the indeterminate. And, beyond that

even, the constitution of the painting has started to include various and

sometimes conflicting processes, with figures and actions overlapping.

BRUNO DUNLEY

I see that, too. The work since 2015 has been directed towards a freedom, a

flow, something in the sense of what Alexandre called a turning point. And I

think the earlier production, from 2009 to 2013, had something of that

procedure in it of putting down a thick layer of paint, scraping it and

interfering with it.

AW

There were about three procedures…

BD

... that appeared in the paintings every now and then. But I think the main

point is that in the course of making the paintings there is a kind of

separation between my impulse to make, in what I want from and think of the

work, and the result of the painting. In the work made between 2012 and

2013, it’s clear to me that there was something missing, a great

disconnection between what I wanted the works to be and the results. There

was a relationship between the faded colour and that thicker material that

could silence the recognisable images that identify the world, but what I

realised then was that instead of creating a silence that could widen our

perception of time, those paintings produced something mute and sterile.

Noticing this sterility in the work created a desire in me for movement and

displacement. I reflected on the possibility of reaching a greater chromatic

potency that wouldn’t carry such a codified narrative of colour. I wanted to

experiment with colour to invent a narrative.

I started researching a series of chromatic experiments from throughout the

Middle Ages, the illuminated manuscripts etc., and dedicated myself to

painting and drawing on paper. This practice, which I began in 2015, created

a freedom in terms of the ease of the medium, the scale, in being able to

rip up and throw away. I think I still carry a few things from that previous

process. But, in partially eliminating the figurative model that was

structuring the composition and suggesting a means of interpretation, the

work risked falling into a void and having no place. You start dealing with

an idea of abstract painting that is very complex, very spent. How is it

possible to construct images without referencing images? With painting

coming to the foreground the methods and the processes start to become more

relevant, but an image is still being formed.

AW

But I see that for a while you still maintain these two ways of starting the

paintings: sometimes starting from a more recognisable figure, other times

letting the painting be more prominent in the process.

JAR

Yes, I said there was a change, but I didn’t mean a complete break. Because

certain characteristics remain, they turn up here and there. For example,

striving to completely fill the surface, structuring the painting around a

strong central motif… Aside from that, I think the painting is much freer,

which, for me, is evident in the series

Bestiário

[Bestiary], which the

Dilúvio

[Deluge] paintings are a part of.

BD

Bestiário

also comes from the Middle Ages imaginary that I started working closely

with in 2014, through the illuminated manuscripts. In that series, I think

the sense of freedom grew to such an extent that it caused other problems

for me, because until that point I had always tried to find a balance, so as

not to go too far. If you go over the top, if you stretch the rope too far,

you’re left with something kind of undefined. So, it’s an ongoing conflict –

to find some measure between freedom and restraint, especially in the

pictorial gesture. The idea of the gesture is still an open question.

The gesture in the history of modern and contemporary abstract painting is

the protagonist in a narrative of conflict between the expression and

negation of a lyrical subject. I don’t believe that art is made to express

absolute freedom of will, but at the same time it happens through the

artist’s desire and their attempt to capitalise on a thought, a thing, an

expression. The

Dilúvio

paintings are unfolding of these conflicts, which have been ongoing since

the work began, in 2006. So, what I am trying to understand is the

possibility of expanding the pictorial experience so that it isn’t led by

expressive gesture alone, but also by other ways of making that are just as

worn-out. This idea of expansion is important to me. It’s still vague, under

construction, but it is moving towards introducing an experience of

dislocation, of transformation, of expansion, in terms of perception.

Creating a reflection on the relationship between our body and the painting

and the world we live in.

Bestiário

was the most illustrative point of my career and I wasn’t afraid of taking

an iconography from imagined worlds, from psychological fears and

mobilising my work in that territory. The concerns I had before about

gesture, about what painting is, of what it can be and how it has been

positioned in our time created a tension between the experience of my body

and a culture inherited from my education. This conflicting relationship

with a culture that was constructed, approved and sanctioned by a portion of

society was dissolved and introjected int0 the work. In 2016, when I started

the series, Brazil was going through a complicated period which changed the

paradigms in the country’s social structure. Our social pact was broken by a

coup d’état orchestrated by the National Congress, the Judiciary, and by a

significant portion of the press and business and of civil sectors in

society, which illegitimately toppled the then President of the Republic,

Dilma Roussef. That still hasn’t been resolved; it’s still a difficult

subject in our society.

What emerged from this was a state of fragility, an antidemocratic spirit

and societal disgust that, through a great national agreement and breaches

of the constitution itself, threw the social pact in the bin. I started to

look at questions about painting, about being an artist and think, “Man,

what kind of problems are these?”. Society was and is going through such a

sudden and brutal change that these questions took up a different space

within me. The 2016 coup was so absurd that this sense of freedom

accelerated and firmly installed itself in my work. In a way, I tried to

deal with the turbid side of what humans are capable of by producing

something terrifying and disgusting, but, even though I produced works that

I really like, I think I failed. That issue isn’t something that can be

addressed and challenged through my language.

AW

Bestiário

also plays an interesting role in what we are talking about. Beyond

everything you just said, I also see these paintings as the formulation of

something that has always gone with you: a kind of presence of discomfort,

of unpleasantness in your work. In the book, in a conversation with Cadu,

you talk about something “slightly nauseous”, referring to that

yellow

monochrome

(made in 2010), which I think is a manifestation similar to the idea

expressed in

Bestiário

and in the paintings in this exhibition (Virá, 2020). It’s as

though this will, that has shown itself in different aspects over time, is

always close by. It’s clear that all the triggers you just mentioned exist –

and the trigger doesn’t always define the places a work can go once it’s

finished, right? If the coup triggered these works, they can also reach many

other places, different to those they started from. In a way, I think this

series kept you close to the idea of unpleasantness that I was talking

about. Saying that, what do you understand by discomfort when looking at

your work?

BD

Discomfort is a good word, because terms like “strange”, “unpleasant” or

“violent” have already come up for me. When I started painting, I wanted to

be a metaphysical artist who worked with intimate colour, the expansion of

time, a kind of slowing down of the urban and media experience. I admired

artists with those characteristics, but in my practice I started discovering

that I wasn’t that type of artist. So, the first discomfort was realising

that I wasn’t a metaphysical artist, of visual repetition, but an artist of

variation, and this, in the context of my training and what I idealised, was

uncomfortable. That has been the case since my first solo exhibition,

Os nomes

[The names], in 2010, but what was at stake was understanding that variation

as a construction of a poetics, of a place that passed through meta-painting

and that said something about the condition of painting.

I perceive this discomfort in a few ways. One is in this variation that

repeats itself in the exhibitions. I really value the autonomy of each

painting, the fact that each one of them has a body, a physicality, an

autonomy of language. But putting them in an exhibition space with other

paintings, which also have their own autonomy and difference, caused

confusion, discomfort. The variation in the appearance of the paintings

caused a conflict that interested me. I understand conflict as a field with

two possibilities: dialogue or war. Both have a political aspect. I think I

went down that path within the work, in the relationships between the

paintings, between the exhibitions, and that was stimulating and at the same

time uncomfortable. It isn’t anymore. It’s beginning to settle and to assert

itself.

JAR

We’ve been talking until now about changes the work has gone through in 10

years of Bruno’s career, and I was reminded of a few adjectives often

attributed to his work, which, according to these classifications, is

heterogeneous, diverse, plural. There’s a reason for that, certainly. But I

also think that this variety of images, solutions, gestures and processes

doesn’t mean eclecticism. There is a lot of working out in this

multiplicity, of something attempted; a spirit of testing many

possibilities.

With that, the idea of a collection of images has accompanied the

progression of Bruno’s production since the beginning – the idea that the

work comes from collections of images, whilst at the same time, through his

decisions, it creates a collection of images. This collection, in a sense,

anticipates not only figures, but also the reasoning, the ways of thinking.

It hints at the fact that the work results, in part, from studies of various

images that go beyond the field of art.

So, in fact, there were always big differences between one painting and

another every time the work was shown together. Now, these differences, or

what which you described as “conflict”, appear in the same work. Today,

every painting is more composite than before – sometimes, as I said,

apparently contradictory motifs and processes emerge side by side on the

same canvas.

Another aspect of this variety informs the erudite nature of the work –

cultured, studied, enlightened. But not because it makes direct references

to other artists, but because it internalises an interest in the history of

art and seems reinvigorated, even, in the study of that discipline. What I

want to say is that there are obvious conflicts here with certain works,

with certain artists, but also with the history of art.

But, returning to the question, it’s interesting to think about the plural

character of the work, considering also that Bruno’s process now is not as

planned out as it used to be. The fact that the work now goes into battle

without any, or with many preliminary materials used at the same time,

widens the margin for the unexpected. If the work once seemed to repeatedly

erase the previous steps in its process, to deal with an apparently ever

wider repertoire of choices, it now seems every time to be seeking to

establish conditions to create a painting that is, above all, free and at

ease, from the beginning through to the end of its production; a painting

that still deals with pre-existing, borrowed materials, but through an open

action, without being tied or committed to this or that author, to this or

that strand, to this or that painting tradition.

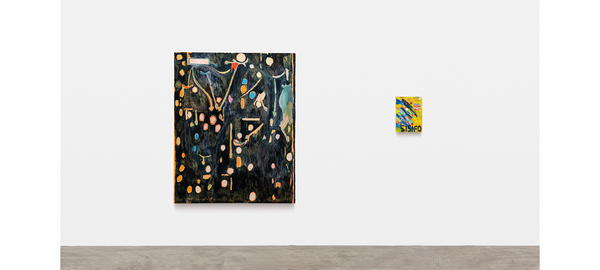

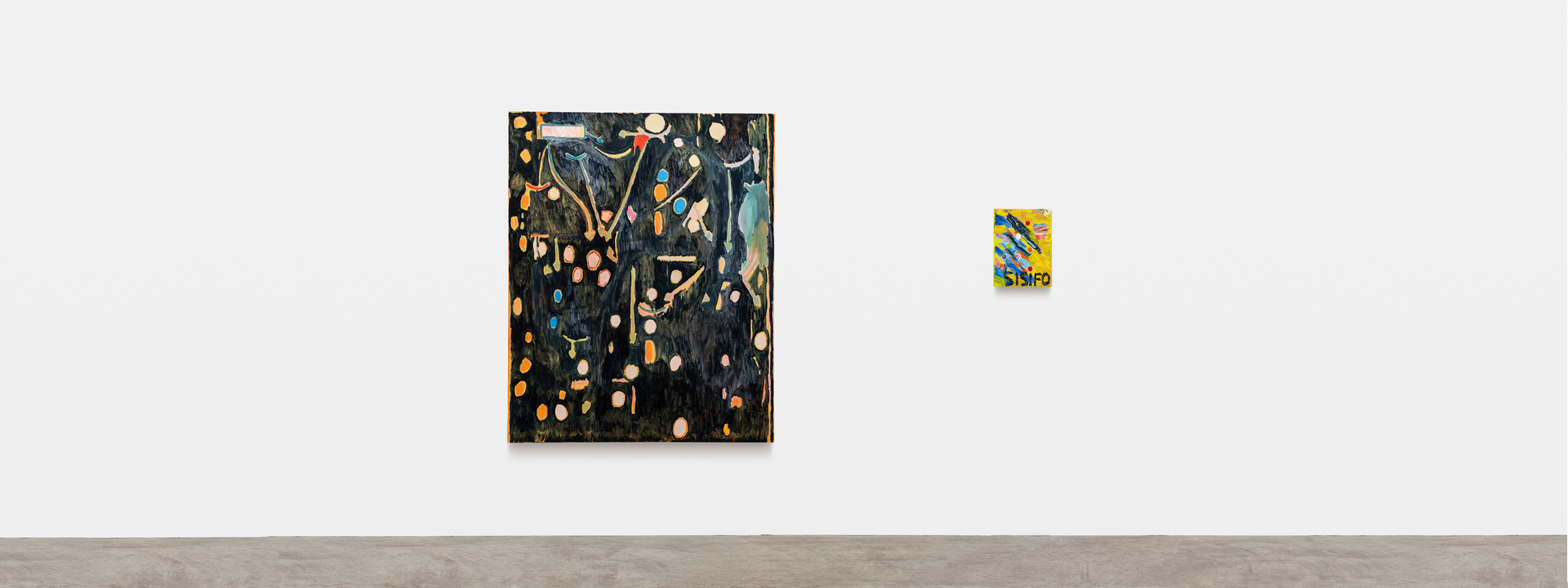

On a canvas like

Cabeça de ferro

[Iron head] (2019), for example, there is a central element that recalls

Leda Catunda’s rivers, a lower area reminiscent of Jorge Guinle’s paintings,

the border with prints that perhaps refer to Jose Leonilson’s work… They are

different materials that contribute to the construction of the painting,

which, I repeat, seems at ease in dealing with the vocabulary of these

artists, without bowing to them – on the contrary, it’s done in a manner

that is free, without prior planning, without having to adapt the images,

without being committed to a specific language or genre.

AW

You also get yourself into trouble, in a good way, which has a lot to do

with this change of procedure. You try to free yourself from many things to

paint – both in the exercise of thinking about the work from a certain

distance and in the moment at the studio. And I believe the position you put

yourself in has a lot to do with a kind of

anxiety. You are always trying to get rid of your reference

points, considering that you, more than in a lot of other cases, begin a

painting with

many

points of reference, as Zé just said. A vast collection of procedures, a

vast collection of references, a vast collection of images from the world.

Then comes the effort of, little by little, getting things out of the way,

and we know how complicated that is. Because I know that you get to a point

– which could be true or false – where you are kind of left with nothing and

think, “Damn, now what, what do I do with this thing I just made?”.

That could be done in an anecdotal way, it could be an ironic, jocular

comment, but I don’t think that’s what you do. When you use

dripping,

for example, I don’t think you’re accessing a way of painting like someone

searching supermarket shelves for an available procedure. I see it as a

possible reflection of a struggle born from trying to clear the field.

JAR

The entire process ends in being snookered.

AW

You always end up snookered. It’s a very important starting point and I

think that anxiety

is in

the paintings, relating directly to the discomfort we are talking about,

this uncomfortable thing that we’re not sure how to define, or where it is.

BD

I think everything you’ve put forward exists in the works: an idea of a

collection of images, a collection of the possibilities of painting, and in

that sense, I’ve been interested in what painting can be since the

beginning. But it’s worth pointing out that there is a reduction there,

because I don’t deal with the field of painting in a broader sense. I deal

with what painting can be as this traditional method, paint on cloth, what

painting can be today and after all its history, of a questioning about its

power to respond to a post-industrial world, mediated by photographic

images, TV and the internet. What I was thinking about more were questions

of a certain history of art and the development of painting as a human

expression in other contexts and periods. I already mentioned the

illuminated manuscripts, but I am very interested in cave painting, in

Egyptian painting, basically, it’s a very diverse interest, but still within

this field. It’s a passionate interest. I don’t explore it in a very

studious way and I don’t write about it either. My academic life has been

short. I don’t do systematic research, but I do like to look at and read

about these things.

JAR

Right. But you do also systemise your thinking, for example, to give

classes…

BD

My interest in teaching comes from the possibility of creating spaces to

carry out these studies, to provide myself with another trade, a stimulus to

organise ideas and look at them with other people. I feed off these meetings

and try to create open approaches where everyone has a voice and can share

their knowledge and research. Although these experiences are very varied,

there is a point where everyone has an idea formed about the world and

stories of art. I believe everyone has the right to knowledge, but for there

to be access and construction, there have to be opportunities and interest.

There is a whole field of validation and diffusion of knowledge that goes

through social structuring in order to form and circulate ideas. You need to

conquer or create these physical spaces – texts, publications, universities,

museums, cultural centres – to conquer people’s imaginations. I think this

construction is stronger when the game is open, when the material

possibilities of that construction are more approachable and when the spaces

of access and power are shared.

I want my painting to reach something of that public dimension in a way

that is at ease, as Zé put it. For it to go out into the streets, you know?

For it to be something common and public, not just in the sense of access to

its physical presence, but in the circulation of ideas, of a sensibility, of

a pulse. I think I try to do this on an intimate scale inside the studio,

and I am increasingly interested in participating in this construction in

the public space, in the possibility of contributing to the existence of

these spaces of expansion.

JAR

Bruno, let’s get back to the impact the coup against President Dilma

Rousseff had on your production. Firstly, I admire the fact that there is no

discursive reaction in the work to the episode that mobilized it – the fact

that your production doesn’t confuse non-conformism with a propagandist

expression, of slogans or emblems. On the contrary, the work seems to

internalize this non-conformism in the forms of the painting. In any case,

what really caught my attention in what you said was this association

between the breakdown of a social and political pact and the freedom you

said took you away from the “questions about painting” you had been

struggling with before. My question is: what thoughts, what parts, what

principles in the work were tied to the Brazilian social and political order

before? And how do you see art and the possibilities of its inclusion in

Brazilian society today? How do you perceive art’s place in today’s society?

Would you say that there is a specificity to the language of painting in

this context?

BD

I agree with what you said about the work not having gained a discursive

dimension because of a political episode that affected the lives of the

entire Brazilian society. But, for me, it was disturbing to realise that

this breakdown of the social pact also caused tensions in structures of

legitimation, in terms of how art is perceived, of its place in society, its

circulation and of a politicization of taste in the visual arts. This has

intensified since 2016, and I think this path led towards a deeper awareness

of what it is to be a citizen, which led me to another awareness of what it

is to be an artist. I don’t disassociate these two states and I came to an

understanding that didn’t exclude the autonomy of each of them. The

questions of the language of painting, of the image and its stories, remain

fundamental in the work, but today they exist alongside questions about

social and cultural structures, which were always precarious, insufficient

and exclusionary. It seems contradictory, because it’s as though, out of a

socially traumatic experience, my experience as an artist individual

accelerated, and something in that reflection on questions specific to

pictorial language lost its importance, at the same time that it started to

act more powerfully within the works. This, which was already in conflict,

dissipates and what is left is this layer of thinking about how art or

painting is put to work in society, how it is stratified in the mechanics of

a constrained cultural apparatus that encompasses its production,

circulation and the way it is appreciated.

JAR

One of the motivations, then, was to extrapolate or break down the limits of

this stratification?

BD

I don’t know if it was to extrapolate those limits, because that’s a very

big thing and goes beyond my individual experience. It needs to be a

collective and public effort. What I want to say is that I found myself as

an artist who has had the opportunity to be trained in art at universities,

institutions, artist studios, who spends time with other artists of various

ages, who has seen many exhibitions, who has had the privilege to travel to

see art… My training, despite being very centred on a portion of Brazilian

modern and contemporary art, has a European and North American bias. A part

of Brazilian art has this bias, and has been struggling with that for at

least a century. I had to look at the space I occupy in society, at the

cultural structure that formed my visual thinking, and understand that I

play a part in a collective historic process. How does visual arts organise

itself materially within our society? How is the diffusion of that imaginary

organize? I would say that art’s place in society is in construction, in

collaborating in the construction of the imaginary of an individual, of a

group, of a country, or the world. The field of visual arts is still very

separate from Brazilian society. We have a market that is structurally very

strong, but with low numbers of representation in relation to the number of

artists today, and which largely does not mirror the diversity of Brazilian

culture. The institutions are highly dependent on public-private

partnerships to keep going and this is a reflection of an absence of public

policies for the sector. The outcome of this is a kind of hijacking of the

possibility of a broad and democratic construction of this imaginary through

the visual arts. There have been periods where this was thought about with

more public intentions, but that were no less class-based in their

structures. The whole of Brazilian modernism from the 1920s to 1950s,

neo-concretism, tropicalism, the magazines

Malasartes

and

A parte do fogo,

the participation of Paulo Sérgio Duarte, Ferreira Gullar and Iole de

Freitas in FUNARTE, and INAP (Instituto Nacional de Artes Plasticas) at the

end of the 1970s and start of the 1980s, were initiatives that opened up

spaces for modern and contemporary art to circulate and be debated.

I don’t think painting having some commitment to the specificity of its

language is so relevant today. Modernity has already achieved that. We

already understand painting not only as representation, but also as a

manifestation of ways of making, of temperaments that emerge through the way

you manipulate the materials, the tools, the matter…For me, the commitment

to these specificities should be worked on more in the area of education, in

ways of spreading culture and knowledge. The autonomy of art was one of the

most important achievements of modernity, but it needs to be spread without

seeming alienated from the processes of being a citizen, separated from the

social and cultural realities of the people.

JAR

Was that what drove an understanding of artistic practice guided by a

“Western”, European, North American tradition?

BD

Not exactly. What drove that understanding was an idea of violence, which is

still very diffuse for me, and I don’t identify this presence as a

characteristic of Brazilian painting. Violence is an important element of

Cinema Novo, for example. The language and presence of Glauber Rocha, who

also addresses this in the text “Eztetyka da fome [Aesthetics of hunger]”,

is violent. I think what drove it was a stronger feeling of something I had

already seen in the sociality and in history of Brazil:a society that

believes in punishment and violence to resolve the most diverse social

conflicts and which has never managed to reflect broadly on historical

phenomena like slavery, oligarchic rule, the military dictatorship, etc. The

product of this is a societal culture that is enslaved, racist,

authoritarian, chauvinistic, built on a logic that is punitive,

inquisitive, colonialist and genocidal in relation to Amerindian peoples

and the black population. The understanding came from discomfort with

reality itself and from the need to respond to this with the language of my

work, in a way that is non-conformist, but also non-propagandist. So, it’s

kind of this place that made me uncomfortable. We need to change further to

get out of it. It’s our condition that needs to be mixed up.

AW

When you talk about your desire to be a metaphysical artist, working with

intimate colour, with the expansion of time, and about it being

uncomfortable to discover that you were maybe a little stranger than the set

model at that time, or that the paintings gained strength in that they moved

in a more conflicting, less peaceful place, I still don’t know if discomfort

is the exact word for what we’re talking about. I actually think that the

difficulty in finding this refers to the place that a very interesting part

of your work comes from. You were becoming more at ease with existing with

this strangeness and with these differences, right?

BD

That’s right! I think I was becoming more at ease in creating my work, at

being open to what was happening inside the studio. I’m not an artist with a

very defined plan or idea about what to do, but I’m also not an artist of

chance. So the work has that element of the day to day, of pauses, of

reflection and adjustments that form the paintings. It’s from what I do,

reflect on, accumulate and discard that things happen. I’ve been producing

work for almost fifteen years, and it feels like I’m starting now.

JAR

Around 2010, one of the qualities of the work, in my opinion, was the

anguish that the paintings allowed us to glimpse, something of “I can’t go

forward, I must go forward”. Beyond that, the work carried a great deal of

historical weight in each canvas that was shown. It wasn’t suffering, but it

was evident that the painting went through impasses. And what I see today

looks like an “anxious object”, to borrow Harold Rosenberg’s term. Anxiety

of the kind that doesn’t allow itself to be satisfied, while risking

different directions to construct just one image.

It’s also this anxiety that turns the process of making them visible. The

accumulation of diverse solutions is grouped together in different parts of

the canvas, with a result that is somewhat open-ended. There are many

markings that look like the start of a filling in of space, something that

wasn’t finished, there are many open forms without contours. All this

suggests anxiety, as if the work was interrupted, rushed, in the middle of

its processes, still in the fervour of labour. And this open, ignited,

switched on aspect gives the work vivacity. Nothing arrives ready, complete,

finished, it arrives with points still to be joined together. This might be

one of the principal qualities of the work today. Without trying to create

a hierarchy, “yesterday was better”, “today is better”, I think these

differences are well marked out, at least for me.

AW

I also think there was a change in the construction of the works that

favoured this type of making. In earlier paintings (2015/16/17) you can see

that Bruno used bigger brushes, broader strokes, sometimes resolving a large

area of the canvas in just one action. I think the final layer of paint

seemed faster. Some works were even made in a single session. In some of

these new paintings (like

Fuzileiro

[Marine], 2019) you seem to make the opposite movement. You increased the

scale many times, working with more diluted paint, smaller strokes, with

more layers, in more sessions. It seems like you’re not even expecting there

to be one movement that will resolve the whole painting at once. Some were

even left in the studio for a while, waiting to be resolved. That changes

the game a bit, living with a painting for two or three years... That change

also seems to go in the direction of various points that Zé mentioned, as

though they fostered contradictory questions and procedures existing in the

same work simultaneously.

In the paintings there seems to be an accumulation of “things to be

resolved”. They’re not a calculated project: it’s as though a transmutation

happened in the individual’s relationship with the painting, a chemistry

took place, and inadequacy became the method. It’s neither an existential

issue, nor an affective issue, but an originally formal issue. If the

paintings are a grouping of conflicts that coexist with no intention of

pacification, I think they support themselves by this mismatch, that’s where

they draw their strength. The idea of the work forgetting a little about the

conclusions of the earlier paintings can be really powerful, despite the

difficulty that this movement brings with it. There is something in the

paintings that gives the impression that you had to forget what you

got right

in the earlier work in order to start the next. We could relate this to a

feeling of constriction, as though you were gradually trying to invent a

place with no exit, to find a new path from that. The paintings seem to deal

with an idea of exhaustion. As though the gesture of making something

consumed that thing the moment it was finished, with no sense in repeating

that process, or repeating that painting. You always have to move on to

another.

BD

I think this has to do with the idea of keeping something alive, something

that I’m still trying to elaborate. Maybe this idea of exhaustion and of

inadequacy as a method is already in the language of the work.

JAR

I want to go back to a few points to distinguish what I called erudition and

which you, Bruno, understood as a technical skill. When I say the work is

cultured, erudite, I’m thinking about the information of the repertoire,

about conceptual knowledge, beyond the technical part of making, that inform

the production – and none of these traits exclude your desires to be

commonplace, for the paintings to have a presence on the street, too, as you

said. But as far as making the paintings goes, I think an important

characteristic of the work, is letting the limitations of your dexterity, of

your technical skill, remain evident, on show, exposing them openly, in

processes that are also ingenious and unexpected. It’s more or less when the

imperfect, the inconclusive, or the dissonant, when the accidents, the

crudities coincide with the idea of vivacity, above all because they result

in sudden decisions, which in turn invigorate the results. Anyway, as Ale

said: the work is more open to the unplanned, and the technical limitations

appear in a frank way, they constitute the work – the accidents, the smears,

the smudges, the discontinuities, the leftovers on view.

BD

The valorisation of technical skill is related to the sense of constructing

something difficult, a valorisation of difficulty as a value to be admired,

a very clear distinction between managing to make something special, or not.

The same reasoning would serve to talk about erudition. I prefer the idea of

vivacity, because it relates to the idea of open processes, of having a

freshness which I identify as an ethic of making, almost an ethic against

skill, against hiding how the thing in front of you was made. This also

comes from my training, from my understanding of the concretists and

neo-concretists, of the Russian vanguard, of the North American minimalists,

of artists like Amilcar de Castro, Vladimir Tátlin and Donald Judd. I think

I have inherited something of that thinking, which appears in an

aesthetically opposite way in my work, because it appears through

accumulation and not from a synthetic procedure with an industrial clarity.

It appears in a chaotic way that is difficult to apprehend immediately, and

perhaps the movement it demands from perception is what relates to vivacity.

AW

About this possible lack of technical skill, I think that also plays a part

in the type of variations that the paintings carry, in the differences

between them. There is something a little “awkward” in each of them which

means they’re not obedient to a highly planned strangeness. The works

generally exist in two places at the same time: the strangest ones store a

little of the most tranquil ones, and vice-versa.

BD

I wouldn’t say they’re strange and tranquil, but strange and beautiful. I

can’t separate the two things. But this keeps moving, and goes back to the

question of apprehension and vivacity. I’m searching for a terrain that is

not so stratified, and there is an element of risk there. I find it

interesting for it not to be given to such pre-established conceptions,

because the perception of the paintings changes. I try to put them in a

place that is open, where everything that could be definable coexists with

things that I still don’t know.

JAR

The title of the exhibition,

Virá

[It will come], also suggests something transitive, looking forward.

BD

I think all the exhibitions I did from 2014 to 2020 were attempts to move

myself away from the perception I had about my work that was shown in the

exhibition

e

[and], 2013. That produced something for me that was dehydrated, sterile,

mute. I think I’ve only just come out of that perception. These are

paintings that emerge from that journey, and I think the title,

Virá, declared at such a horrible time – the pandemic, the

advance of the extreme right, disastrous political processes in Brazil and

in the world, withdrawals of rights and social achievements – shows that my

position is of fighting, of transformation and possibility. I live this

position, and not only within my studio. I live this in my actions, in the

way I move within society, in the things I do beyond painting, with the

people with whom I construct another place in micro-political dimensions,

but that is growing. What we are living through today is pendular, it will

pass and I think civil society has an important role in this historic

process. It’s our responsibility to formulate a new social pact. So, I see

it from a perspective of construction and work. There is a lot to do, in my

painting, between people, in the relationships in the art world – that

excites me.

This text was developed from two conversations held on September 2020 at

Bruno Dunley’s studio and the exhibition

Virá, at Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo.